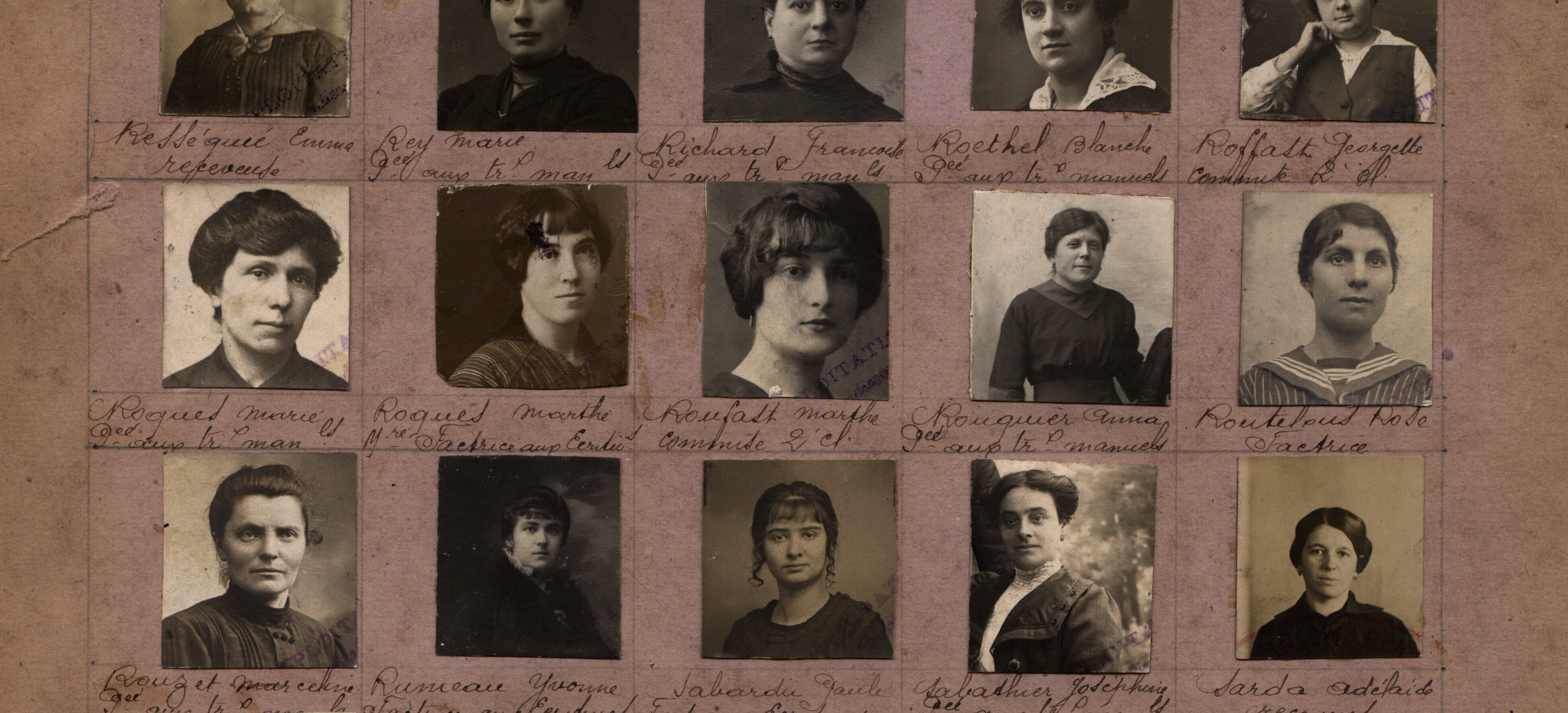

The oldest female professions

In the early days of railways, jobs were implicitly reserved for men for several reasons: the importance of physical labor, continuous work organized in alternating shifts, long-distance travel away from home, a concern for authority over subordinates and respectability in front of the public, and a fear of disorder that could result from the proximity and mixing of genders. Nevertheless, companies hired women for certain jobs, either due to the scarcity of male labor for unskilled jobs, to assist widows of employees, or to obtain a low-cost workforce. The oldest documents preserved by the National Center for Personnel Archives on female railway workers consist of service records of women born between the 1820s and 1850s who entered the railway industry between the 1860s and 1880s. They held positions such as stationmasters, gatekeepers, and very often, sanitation attendants responsible for the care and maintenance of facilities in the stations.

Many of these women were widows of employees who had died while on duty. Indeed, it was preferable in the eyes of the companies, as expressed by Frédéric Jacqmin, director of the Compagnie de l’Est in 1867, “to come to the aid of the widows and daughters of its former employees and to replace an always insufficient and difficult-to-receive charity with honorable work.